Los Angeles does, contrary to what some believe, have seasons; they just aren’t the same as those in the Northeast or Midwest. There isn’t really a fall or a winter. Instead, there’s Fire Season, Rainy Three Weeks, and June Gloom, among others. But there’s another way to measure the passage of time: by fruit. We’re not talking about what’s in the farmer’s markets, but what’s growing on the streets, in parking lots, in plots of land that may or may not belong to anyone.

Los Angeles, especially the hotter, drier East Side, is not home to an unusually large number of native edible plants, but it is home to an absolutely berserk amount of non-native fruit trees, planted both intentionally and accidentally. Many of these simply line neighborhood streets. Among them, especially prominent on the East Side, in now-trendy neighborhoods like Silver Lake, Echo Park, and Atwater Village, is the loquat.

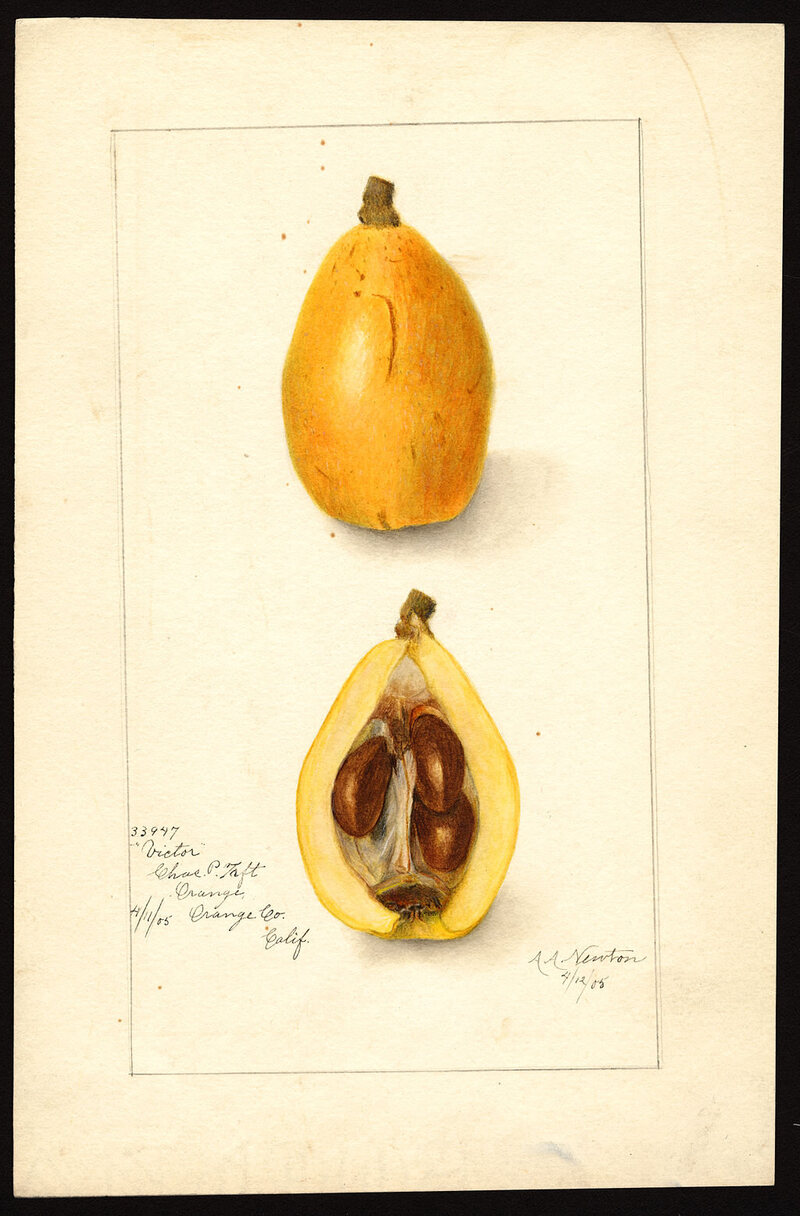

The loquat—an extremely juicy, incredibly prolific, mighty delicious sweet-sour fruit, bright yellow in color, somewhere between a plum and a mango in flavor—is so common that you can hardly walk more than three or four houses in these neighborhoods without passing one. And yet it isn’t celebrated, prized, or, for the most part, eaten at all. You can tell this because if they were valued, then all those trees wouldn’t be absolutely heavy with fruit. “Nobody eats them,” says Alissa Walker, a Los Angeles–based journalist and loquat enthusiast, of the loquat trees in her neighborhood. “They just hang on the trees, and I’m like, ‘Is anyone going to eat these?’”

Loquats are not, despite their name’s similarity to kumquat, in the citrus family. They’re actually in the rose family, which also gives us apples, pears, and stone fruits. The tree can be anywhere in size from a large shrub to 30 feet high, and is extremely attractive in a subtropical way, with dark, glossy green leaves. It’s native to southern China, and also has a very long history in Japan. When the Portuguese became the first Europeans to land in southern Japan, in the mid-1500s, they established commercial trade between the two empires, and brought the loquat back to Europe. From there it spread to essentially anywhere warm: the entire Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, parts of West Asia. The Spanish found the loquat grew especially well for them—the country is still a major producer—and brought it to their warm colonies in the New World. Throughout Latin America, the loquat was planted, and grew, and produced lots of fruit.

Loquats are very easy to grow. They’re evergreen, and don’t require much water for a fruit tree, which makes them ideal for places with a lot of sun and not a lot of water. (Los Angeles is a perfect example.) They can tolerate just about any kind of soil as long as it’s not too salty, can handle high elevations with no trouble, and can even be planted from seed (though the fruit from those loquat trees may not be good). Grafting—basically inserting a loquat branch into a cut on an existing tree—is the preferred method, and you can graft loquats onto the trees that produce pears, apples, quince, and most of the other rose family fruits.

They produce an almost overwhelming amount of fruit with basically no care or effort. Leave them alone, in shitty soil and with hardly any water, and each spring, you’ll get more fruit than you can possibly eat. Huge bunches of golden, plum-sized fruits, easy to pick (no knife or tool needed), with edible skin, perfect for snacking. And in Los Angeles, it’s common to see trees with branches buckling and bowing with the weight of these bunches. Nobody picks it. Whatever the birds, squirrels, and racoons don’t get to simply falls off and rots on the ground.

Walt Disney changed the path of the East Side of Los Angeles in 1925, when he placed his first studio in Silver Lake. By the late 1940s, the studio moved to the north, to Burbank, but Silver Lake had become established as a home for actors, especially LGBTQ actors. By the 1970s, the neighborhood, close to downtown Los Angeles, grew to embrace a mix of artists and recent immigrants, who lived there for its affordability and proximity to factory work downtown. Those immigrants were primarily from Latin America, and especially Central America: Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua.

When the Spanish brought the loquat to their Latin American colonies, the fruit became a major part of Central American culture. Central America is fruit heaven; in addition to native papaya, passionfruit, and guava, the Spanish (and later the Americans) used the rich tropical environment to grow a massive array of flavors and colors. The loquat, which is called níspero in Spanish, is common in these countries. It’s typically eaten fresh, the large seeds spat out, and sometimes made into jam. (It has an extremely high pectin content, which allows jams to set easily.) San Juan del Obispo, in Guatemala, has a loquat festival each year.

Those Central Americans, when they came to Los Angeles, planted the loquat in their yards and gardens. Though this part of Los Angeles is much less humid, more desert-like, than Central America, the loquat thrives there, unattended, as well as it does in Central America. (Other tropical fruit trees in the area grow just fine, but may need a large amount of added water and sometimes for the soil to be amended.) The loquat trees sprung up all over the East Side, providing a taste of home (and free food) to those new to the city and their descendants.

Loquats are unusually early-ripening fruits; they’re ready to eat by springtime, starting in late March, though the season lasts, unlike with citrus, for only a few weeks. They are, for a particular kind of Angeleno, the marker of the end of the rainy season and the start of spring. “I have two kids, and for them, everything is about seasonality, right? What’s the next holiday or whatever,” says Walker. “So it really has become, for them, this real springtime thing. They’re really big on picking them, they know where the trees are, we go out with our little wagon. There are so many just on our walks around the neighborhood or on the walk to school.”

This story feels common in Los Angeles. One of the city’s great, weird attributes is its status as a sort of blank canvas. It is a large city where one shouldn’t really exist, low and sprawling outwards. Instead of apartment buildings, on the East Side, in the mid-1900s, there were bungalow complexes clustered around a common outdoor space. And in most of those outdoor spaces, there were fruit trees.

All cities change as new people and new communities move in, but in the denser, older cities of the Northeast and Midwest, there’s only so much that immigrant communities can impact. Businesses change, languages change, but it’s not as if apartment buildings in New York’s Chinatown or Chicago’s Portage Park are torn down to make them more like buildings in China or Poland. In Los Angeles, though, planting fruit trees from home, wherever home was, has long been an affordable way to physically alter a neighborhood. Iranian immigrants in Glendale planted pomegranates. French and Italian immigrants planted grapevines Downtown. (There’s still, improbably, a winery there.) Filipinos in Glassell Park and Historic Filipinotown planted calamansi. There are dozens of these stories; just about everything short of arctic cloudberries will grow in Los Angeles, if you give it enough water.

This city has almost been terraformed—the sci-fi term for the process by which humans alter the land, air, and atmosphere of another planet to make it more like Earth. Immigrant groups to Los Angeles terraformed it to make it more familiar to them, or maybe just so it could produce some free food they like.

In many of these neighborhoods today, however, loquats go unpicked. “When we started doing this project, we first catalogued about 100 fruit trees in public spaces, and none of them were ever picked,” says David Burns. The project Burns is referring to is Fallen Fruit, a legendary and long-running Los Angeles art project that creates maps of public fruit around the city—and, later, many other cities around the world. Fallen Fruit was started in Silver Lake, and Burns, a native Angeleno, is a huge loquat fan. To be fair, he says, “Some people do celebrate it, there are some who flip out for loquats, because they’re so good.” But he, like everyone else I talked to, acknowledges that there is an absolute invasion of unpicked loquats around these Los Angeles neighborhoods.

There are no federal or even really state rules about what is and is not “public fruit.” In Los Angeles, says Burns, the rule says that if fruit has breached the barrier between private and public land, the fruit that is in public land is fair game. Basically, if you have a loquat tree in your yard, on private property, but a branch reaches across a fence and out over the sidewalk? Anyone who walks by can, and should, grab some. Fallen Fruit’s maps, which are created by hand on walking tours, do not ask permission to place this public fruit on the map; they don’t need to. They will remove a tree from their list if a landowner asks, but that’s not a common occurrence. Many of these trees—orange, kumquat, avocado, guava, fig, vines like grape and passionfruit, and many loquats—produce hundreds of pounds of fruit each year. The owners of the trees can’t possibly eat it all, and in the case of loquats, may not want even a single one. If you can reach it from a sidewalk in Los Angeles, most homeowners won’t care about you grabbing it.

Street fruit is almost always safe to eat, as long as you wash it. Fruit trees do absorb toxins in the soil, like lead and arsenic, but those are expressed in leaves, not fruit. After all, a fruit tree’s goal is to get you, or some other animal, to eat the fruit (and drop or poop out the seeds somewhere a new tree can grow). The tree does not want you to get sick from eating the fruit; it wants you to enjoy the fruit. That sounds kind of hippie-ish, but there are plenty of studies on urban fruit, and the consensus is that it’s perfectly safe.

But tens of thousands of pounds of public fruit go to waste in Los Angeles each year, simply because Angelenos don’t pick and eat it. There are cultural reasons for that; not everyone grew up eyeing plants, especially in a city, for their palatability. But there are other reasons more specific to the loquat.

Starting in the 1990s and really ramping up in the past 20 years, the loquat-filled neighborhoods of the East Side—most specifically Silver Lake, Echo Park, Eagle Rock, Mt. Washington, Highland Park, Glassell Park, Atwater Village, Los Feliz, and East Hollywood—started to gentrify, and gentrify hard. Wages have risen slower than home prices, making home ownership (and long-term presence in these neighborhoods) harder. The makeup of the East Side changed dramatically: whiter, more affluent, younger, fewer immigrants. “What that wave did was start displacing certain communities that had cultural and ethnic communities that were multigenerational. Within some of those communities, certain fruits are really coveted, and that’s what you find with loquats on the East Side of Los Angeles,” says Burns.

The new residents didn’t plant the loquats. They mostly didn’t tear them out, either: They’re pretty, and that’s expensive. But the loquats weren’t their choice, and it’s fair to say that many Americans, if they don’t have cultural ties to a place that values the loquat, have no idea what it even is.

Loquats actually have a longer history in Los Angeles than even the street trees in the East Side. Ads in the Los Angeles Times starting in the late 1800s hawked groveland that included loquats. A 1906 article exclaimed that six varieties were available in Los Angeles markets, and that demand for the fruit was booming. That was largely due to the efforts of one C.P. Taft, a fruit grower in Orange County, who loved loquats and was at the forefront of trying to make them commercially viable in the United States. He created several new varieties that did very well in Los Angeles’s climate and soil, and for a little while, loquats looked like they might be the new big fruit on the scene. A raw-food-loving free sex cult called Societas Fraterna loved them so much that they bred their own variety, originally named after the founder’s pseudonym. Today, it’s called the Golden Nugget loquat, and is quite common.

This wider appreciation for loquats did not last long. By 1924, the Times called it “a fine fruit that has been rather neglected.” In a 1932 article, they wrote, “loquats are handicapped by lack of consumer demand both locally and in the few eastern markets to which they have been introduced.” By the 1960s, the loquat was referred to as an ornamental tree, nothing more.

The loquat may produce prodigiously, but it is a fruit almost uniquely unsuited for the American fruit market, which values consistency, appearance, utility, and shelf life above all other attributes. This is the country that created, just for example, the worst apple in the world (Red Delicious) and the worst mango in the world (Tommy Atkins) because they looked good, could withstand shipping and storage, and produced a lot. “The choices about what to consume aren’t made by our parents,” says Burns. “The initial choice of what’s permissible to eat is made by corporations, with a barrier provided by the government.”

Loquats don’t ripen off the tree at all. If a fruit is underripe when it’s picked, it’ll be underripe forever, so you can’t pick the fruit early and ship it while it’s still firm and resilient. It bruises easily, even while it’s still on the tree. This doesn’t make it any less delicious, but the American fruit industry is convinced that Americans will not buy imperfect-looking fruit. It also oxidizes (like an apple or avocado) very quickly, and does not last very long, even in the fridge. And about 30 percent of its weight is waste, in the form of large seeds, which have cyanide-producing compounds in them. (The Italians, to be fair, do make a liqueur, called nespolino, out of low-cyanide-seed varieties of loquat. Also, to be even more fair, you know what else has a lot of waste from seeds, and the same stuff that can break down to cyanide? Peaches.)

All of these factors don’t make the loquat less palatable—imagine a tropical apricot, a tropicot—or easy to eat. It just makes it a lousy commercial fruit in the United States, which is why it can basically never be found in stores, outside of a couple of farmers’ markets and perhaps a specialty store or two that carries Japanese, southern Chinese, or Latin American produce. There’s only one commercial loquat operation anywhere near Los Angeles, in Malibu, and it seems like the farmer grows them mostly out of stubbornness.

For those Angelenos who do love them, there’s no reason to buy them, anyway. They’re free, for a short window, every spring. All it takes is a walk around the block and an appetite.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

"fruit" - Google News

May 27, 2021 at 08:43AM

https://ift.tt/3oRHZ8f

Los Angeles Is Covered in Delicious Fruit and No One Is Eating It - Atlas Obscura

"fruit" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2pWUrc9

https://ift.tt/3aVawBg

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Los Angeles Is Covered in Delicious Fruit and No One Is Eating It - Atlas Obscura"

Post a Comment